Clissold Park, the jewel at the heart of Stoke Newington wouldn’t exist if it hadn’t been for a passionate local campaign in the 1880s to save the then private estate from development. As the last remaining open space in the area, the prospect of losing it to the “jerry builder” prompted concerned local residents to mobilise and lobby various bodies to raise the funds to purchase the park for the public.

Clissold Park, the jewel at the heart of Stoke Newington wouldn’t exist if it hadn’t been for a passionate local campaign in the 1880s to save the then private estate from development. As the last remaining open space in the area, the prospect of losing it to the “jerry builder” prompted concerned local residents to mobilise and lobby various bodies to raise the funds to purchase the park for the public.

The story of the turbulent campaign can now be told for the first time in vivid and dramatic detail through the recent discovery of press clippings, letters and maps, all kept by Joseph Beck, the chief campaigner and faithfully preserved by his family for over 127 years.

This site was created by Amir Dotan; a Stoke Newington historian and member of the Clissold Park User Group, to allow people access to this extraordinary archive, which was kindly provided by Joseph Beck’s descendants. The archive, consisting of 180 items, offers a fascinating and comprehensive account of each step along the difficult journey to secure Clissold Park for public use for ever.

- Explore the entire archive

- Items of special interest

- Joseph Beck’s letters to newspapers

- Clissold Park Preservation Committee letters

- Clissold Park planning maps

- Public meetings

Disappearing open spaces

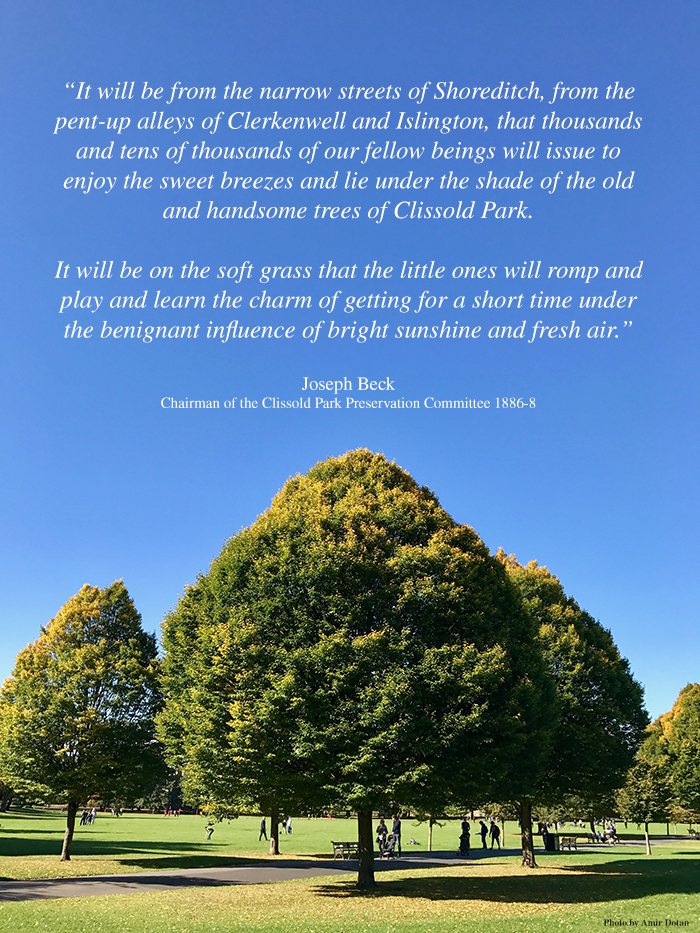

Clissold Park in Stoke Newington is one of Hackney’s most cherished green spaces. The 53-acre park, which opened to the public in 1889, was throughout the 1880s in danger of being built on. Chaired by Joseph Beck; a manufacturing optician from Stoke Newington, The Clissold Park Preservation Committee fought for four years to secure its purchase ‘for the recreation of the public for ever’. Similar battles to preserve open spaces in the rapidly expanding metropolis took place across London during the mid-late 19th century.

The campaign to save Clissold Park

The campaigners felt strongly that preserving the park would improve the health and well-being of people in the area, and also have economical benefits, as the area would become more desirable and increase in property value as well as new homes would result in an increase in the rates the local government bodies could collect.

By the early 1880s, all other open spaces in Stoke Newington except Clissold Park were transformed to suburban streets. The transformation was rapid, and people like Joseph Beck were extremely concerned about losing an open space for recreation where people, especially children and the poor, could enjoy for a little while the fresh air.

The Clissold Park museum in the attic

The long campaign, which consisted of 3 petitions, heated meetings and numerous articles in the press, is usually described in various sources in paragraph at best. An extensive scrapbook, which describes the campaign in fascinating detail, has been passed by Joseph Beck’s descendants through the generations and has been made public in early 2016 via the Amir Dotan’s Twitter account HistoryOfStokey. The meticulously documented letters and press clippings tell the riveting story of how the saga unfolded and the full extent of the drama as the success of the campaign was hanging on a thread throughout.

Many ups and downs

Out of the asking price of £95,000 (about £11,000,000 in today’s money), the committee managed to secure £72,500 from the Charity Commissioners and the Metropolitan Board of Works. In order to purchase the park in its entirety, the rest of the money had to be raised from the local parishes. That proved to be a difficult challenge as parishes needed to be convinced to contribute the remainder.

The committee’s view was that while the park was in Stoke Newington and South Hornsey, as an open space it would also benefit people in the nearby parishes of Hackney and Islington. However, such view wasn’t shared amongst everyone in Hackney and Islington and inter-parish politics, among other factors, proved a major obstacle. Negative views regarding the proposed purchase were expressed and threatened to derail the campaign on multiple occasions.

The strong opposition

One might think people would be willing to pay to preserve 53 acres of open space at their doorstep. In reality, there was fierce opposition, mainly in Islington and Hackney. The main arguments expressed by some people in those parishes against purchasing the park were:

- The money could be better spent

- The campaign was driven by wealthy home owners who didn’t want to see the value of their property depreciate if the park was lost

- Finsbury Park was close enough

- Islington and Hackney shouldn’t be asked to pay for a park which is outside their boundaries

- Rates were high enough as it is

- The park was a ‘swamp’ not worth buying. Islington was originally asked to contribute £10,000.

Following heated discussions that sum was reduced to £5,000 and eventually £2,500. Hackney agreed to pay £5,000. Stoke Newington contributed £10,000 and South Hornsey £6,000.

Happy ending

Finally, in the summer of 1888 all the money was raised and passed to the Metropolitan Board of Works, who purchased the park. It opened officially on the 24th of July, 1889. Sadly, Joseph Beck and John Rüntz, the chief-campaigners passed away two years later.

On the 30th of July 1888, After the park was finally secured ‘for the public for ever’, Joseph Beck wrote a letter to the editor of the Weekly Recorder, in which he offered a heartfelt summary of the campaign and its success. You can listen to it here:

An open space for the public

Since it opened to the public in the summer of 1889, Clissold Park became the recreation ground the campaigners envisaged, offering visitors a chance to to enjoy music by the bandstand, take a stroll along the New River and much more.

Amir Dotan

![20_07_1888 NEWS CLIPPING Clissold Park secured [CHECKED] 20_07_1888 NEWS CLIPPING Clissold Park secured [CHECKED]](https://i0.wp.com/savingclissoldpark.com/wp-content/uploads/2016/07/20_07_1888-news-clipping-clissold-park-secured-checked.jpg?w=333&h=316&ssl=1)